For the past four months, the Jupyter developers – in collaboration with Rackspace, Nature, and O’Reilly Media – have been working on several experiments to give developers, data scientists, and researchers instant access to IPython Notebooks.

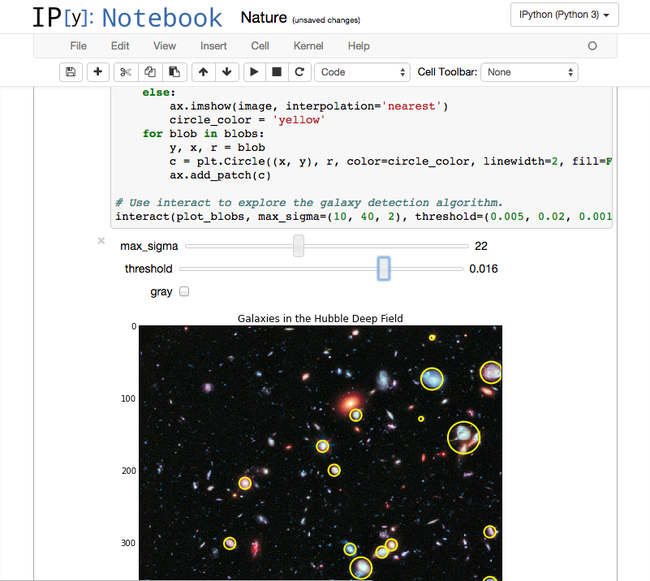

Our biggest experiment so far was a demo with Nature. The journal published an article that featured IPython Notebooks as a tool for scientists to share data and code. The Jupyter team wanted to show off the notebooks to readers in an interactive format. What better way to than to provide a live notebook server to readers on demand?

To do this, we created a temporary notebook service.

How does the temporary notebook service work?

tmpnb is a service that spawns new notebook servers, backed by Docker, for each user. Everyone gets their own sandbox to play in, assigned a unique path.

When a user visits a tmpnb, they’re actually hitting an http proxy which routes initial traffic to tmpnb’s orchestrator. From here a new user container is set up and a new route (e.g. /user/fX104pghHEha/tree) is assigned on the proxy.

Working our way up to the Nature demo, we had several live alpha prototypes around the same time at Strata NYC 2014:

-

Paco Nathan’s Just Enough Math tutorial at Strata, in coordination with O’Reilly Media/Andrew Odewahn

-

tmpnb was announced and used during the very first PyData talk at Strata NYC 2014 by Fernando Perez

-

Olivier Grisel used it in his scikit learn tutorial

After all the above activity, we learned several things:

- Serve static assets via nginx instead of each user container

- Websockets and proxies gobble up ports

- People want to share notebooks

- Pool user containers ahead of time

Static assets should be served via nginx instead of within each user container

nginx is really good at serving static resources. Let it handle the grunt work easily:

location ~ /(user[-/][a-zA-Z0-9]*)/static/(.*) {

alias /srv/ipython/IPython/html/static/$2;

}

This is both for speed and to use fewer file descriptors across the system. We ended up pulling some neat tricks with our deployment setup to mount a dummy user container’s static files into an nginx container. However, if you don’t do this, you get the neat side effect of never having caching problems when launching new versions of userland containers, and even means you could ship different ones to different users!

Websockets and proxies gobble up ports

Each websocket opened by a user ends up opening several ports that will stay open. Since each notebook on a notebook server will open at least one websocket, the number of notebooks you have open directly correlates with the number of websockets.

Here’s some trimmed and commented lsof -i output when a single user is accessing an IPython 3.x notebook server through tmpnb:

# The fixed pieces of networking for tmpnb itself

# Node proxy

node 2646 *:8000 (LISTEN)

# Orchestration layer of tmpnb

python 2669 *:9999 (LISTEN)

python 2669 *:9999 (LISTEN)

node 2646 ip6-localhost:8001 (LISTEN)

# Now for the pieces that each user will be "allocated"

# Established connection with client

node 2646 10.184.2.134:8000->10.223.242.4:53254 (ESTABLI)

# Docker exposes port for IPython notebook server

docker 18173 ip6-localhost:49216 (LISTEN)

# Proxy connects to docker container, keeping port allocated to websocket

node 2646 ip6-localhost:35831->ip6-localhost:49216 (ESTABLI)

docker 18173 ip6-localhost:49216->ip6-localhost:35831 (ESTABLI)

# Docker routes onward to the IPython Notebook

docker 18173 ip6-localhost:49216->ip6-localhost:35673 (ESTABLI)

python 2669 ip6-localhost:35673->ip6-localhost:49216 (ESTABLI)

This got really bad when the notebook server had 3 websockets per notebook and users were opening more than a few notebooks during a tutorial. Websockets have to stay established, by nature.

People want to share notebooks

Honestly, I should know this from working on the notebook viewer. On several occasions, people have passed me links on the demo version of tmpnb, hosted at tmpnb.org.

https://tmpnb.org/user/FKlVK3haOQRF/notebooks/SharingEffects.ipynb

That link won’t actually work for you, because the server is long gone. After a user has left their notebook server, it gets culled. Gone. Caput. Killed. Need to make room for new users and have plenty of fresh sandboxes.

While I would love to enable people to do this, we probably need an alternate way to share these temporary calculations. I’ve used it myself and wished for a way to get it directly on to nbviewer. Posting static content isn’t the same as giving someone the ability to remix your code though. For now, this works and has no bearing on the Nature demo.

Pool user containers ahead of time

Docker can only boot and route so many containers so quickly. To mitigate this, we created a pool of ready to go userland containers. @smashwilson came in and added the spawn pools after we dangled the problem in front of him.

This did introduce problems with initial spawns (Docker failing) and made our introductory experience with a bit to be desired.

We learned this the hard way on boot up, having to code around responses from the API and making sure that we block on our own server instead of Docker.

tmpnb in the wild

We didn’t expect to build a system that would let people create user environments they could use for teaching and tutorials. I’m incredibly humbled that Nikolay Koldunov used it for a tutorial at YaC 2014 while it was still in its infancy.

It’s my hope that people will continue to launch temporary notebook servers, backed by their own tutorial/demo/class content.

- tmpnb repository - Run your own, join us

- Demo images used on tmpnb.org - Make suggestions about the running system